Verdant foliage of along the banks of the Lopinot river, Trinidad.

For most visitors arriving for the first time in Trinidad, their first impressions revolve around the densely forested slopes of the Northern Range hills, which dominate the island’s skyline. A world away from the bustling Eastern Main Road which lies just to the south, this north-easternmost spur of the Andes is home to a unique “natural laboratory” which has become one of the world’s foremost destinations for scientists keen to understand how animals adapt to their environment. But why do biologists choose this far-flung and exotic location to do their research? While visiting scientists are certainly not immune to Trinidad’s vibrant Caribbean charm, the story of one small fish and its natural enemies lies at the heart of the island’s enduring appeal.

The Northern Range is drained by fast-flowing streams, which tumble down from rainforest-covered peaks into verdant valleys strewn with with old overgrown cocoa and coffee plantations. Mini-rapids and waterfalls are an important feature of the landscape, acting as barriers which prevent larger predatory fish from moving upriver. For smaller prey fish, such as the ubiquitous Trinidadian guppy (Poecilia reticulata), this creates two distinct habitats: safe, upstream zones almost devoid of predators, which lie tantalisingly out of reach of the dangerous high-predation environments situated just downstream.

Populations of guppies living in these different habitats have evolved dramatic differences in many aspects of their appearance and life history. For example, male guppies originating from high-predation habitats are smaller and less brightly coloured than their low-predation counterparts. Most obviously, they lack the vivid markings and vibrant spot patterns which play a role in attracting mates, but also make them more visible to predators. The threat posed by predators therefore favours male guppies with relatively inconspicuous colouration. Interestingly, guppies which co-occur with a diverse community of predators also reach maturity earlier and at a smaller size, and produce more, smaller offspring than fish from low-predation sites. These striking differences in life history evolve rapidly; guppies transferred from one environment to the other adapt to their new surroundings at rates up to seven times those inferred from the fossil record.

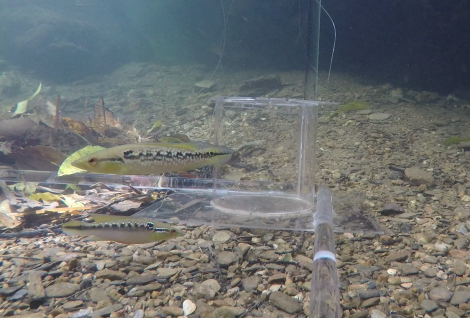

- Pike cichlids (Crenicichla frenata) are one of the most voracious guppy predators found in Trinidad’s rivers and streams. My recent fieldwork in Trinidad mainly focused on these slender, torpedo-like fish, which can attack with a devastating burst of speed.

Predation has also long been recognised as one of the major forces driving the evolution of group-living in animals. In larger groups, approaching threats can be detected more rapidly and the presence of multiple moving targets can help to confuse an attacking predator. Remaining within a shoal also dilutes the risk of being attacked, improving the chances of survival for each individual fish. It’s no surprise then, that guppies originating from high- and low-predation environments differ in their group behaviour, with high-predation fish forming tighter, more cohesive shoals. Recent research has shown that the evolutionary history of exposure to predators shapes the fine-scale social interactions which collectively determine the properties of the shoal, and also influences the dynamics of group decision-making when shoals explore their surroundings.

Blue acara (Aequidens pulcher) – another predatory cichlid found in Trinidad’s streams.

Of course, the attractively simple story of high- and low-predation habitats probably disguises a much more complex picture. Guppies tend to reach higher densities in low-predation environments, and the more nuanced, indirect effects of predation on prey – such as reduced competition and increased resource availability – may play an important role in the evolution of guppy life histories and behaviour. Instead of the stark divide often highlighted between high- and low-predation habitats, there is also increasing evidence for a gradual continuum in predation risk in some rivers. The intensity of predation at a particular site might fluctuate through time, potentially favouring the coexistence of multiple behavioural strategies in prey. Despite decades of scientific effort, there is still much to learn, and little is currently known about the behaviour of the predators which exert such an influence on guppy biology – the subject of a large part of my PhD research!

Further reading:

Magurran, AE. 2005. Evolutionary Ecology: The Trinidadian Guppy. Oxford Series in Ecology and Evolution.

Herbert-Read, JE, et al. 2017. How predation shapes the social interaction rules of shoaling fish. Proc. R. Soc. B 284 20171126; DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2017.1126.

Ioannou, CCI, et al. 2017. High-predation habitats affect the social dynamics of collective exploration in a shoaling fish. Science Advances 3, e1602682.

Deacon, AE, et al. 2018. Gradients in predation risk in a tropical river system. Current Zoology 64, 213-221.

Barbosa, M, et al. 2018. Individual variation in reproductive behaviour is linked to temporal heterogeneity in predation risk. Proc. R. Soc. B 285 20171499; DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2017.1499.